The scarf is the most widely embraced product from French luxury brand Hermès. According to Hermès’ 2024 annual report, the Silk and Textiles division generated €950 million in revenue, accounting for approximately 6% of the brand’s total global sales.

Hermès’ very first silk scarf was created in 1937, exactly 100 years after the founding of the brand.

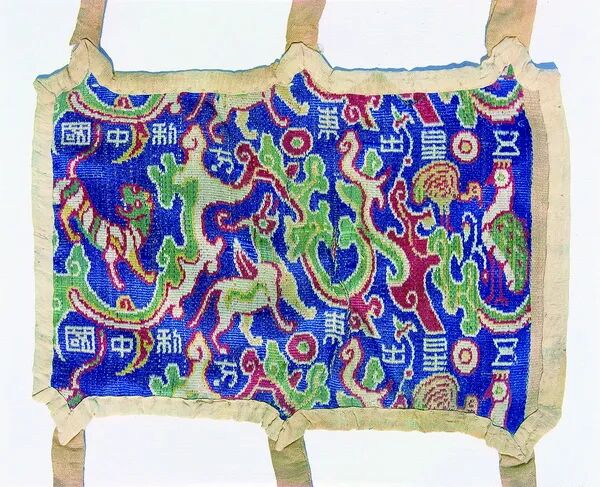

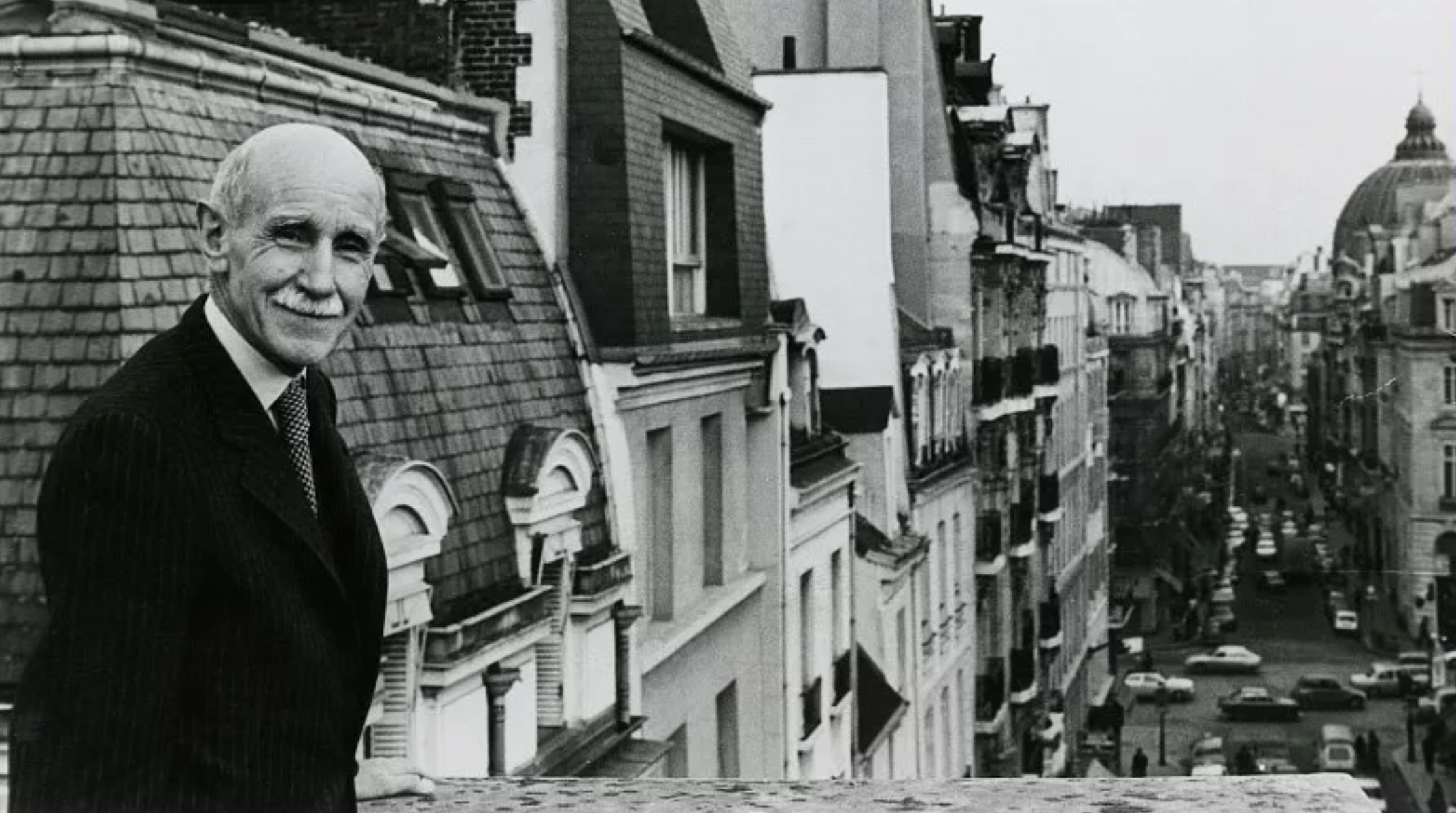

In the 1920s, Émile-Maurice Hermès, the third-generation head of the family business, began expanding the company’s offerings beyond harnesses and equestrian accessories to a broader range of fashion items. He also brought his sons-in-law into the company as partners. Among them was Robert Dumas, who would go on to have a profound impact on the brand as its fourth-generation leader. Dumas was the creator of the iconic Kelly bag and also masterminded Hermès’ first silk square.

This inaugural scarf was titled “Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches,” co-designed by Robert Dumas and artist Hugo Grygkar.

Hugo Grygkar, often referred to as “the Father of the Carré Hermès,” was born in Munich, Germany, to Czech parents. His family later relocated to the Brittany region of France. After meeting Robert Dumas, the two formed a decades-long creative partnership that resulted in many iconic designs.

Above: Hermès’ first silk scarf – “Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches.” The scarf measures 90 cm per side.

Naturally, we were curious – where exactly did the silk for Hermès’ groundbreaking scarf come from?

According to The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles and the official websites of leading auction houses such as Sotheby’s, Hermès’ first scarf was printed using woodblock techniques and crafted from high-quality silk imported from China. This silk was noted for its exceptional tensile strength—twice that of any other silk scarf available on the French market at the time.

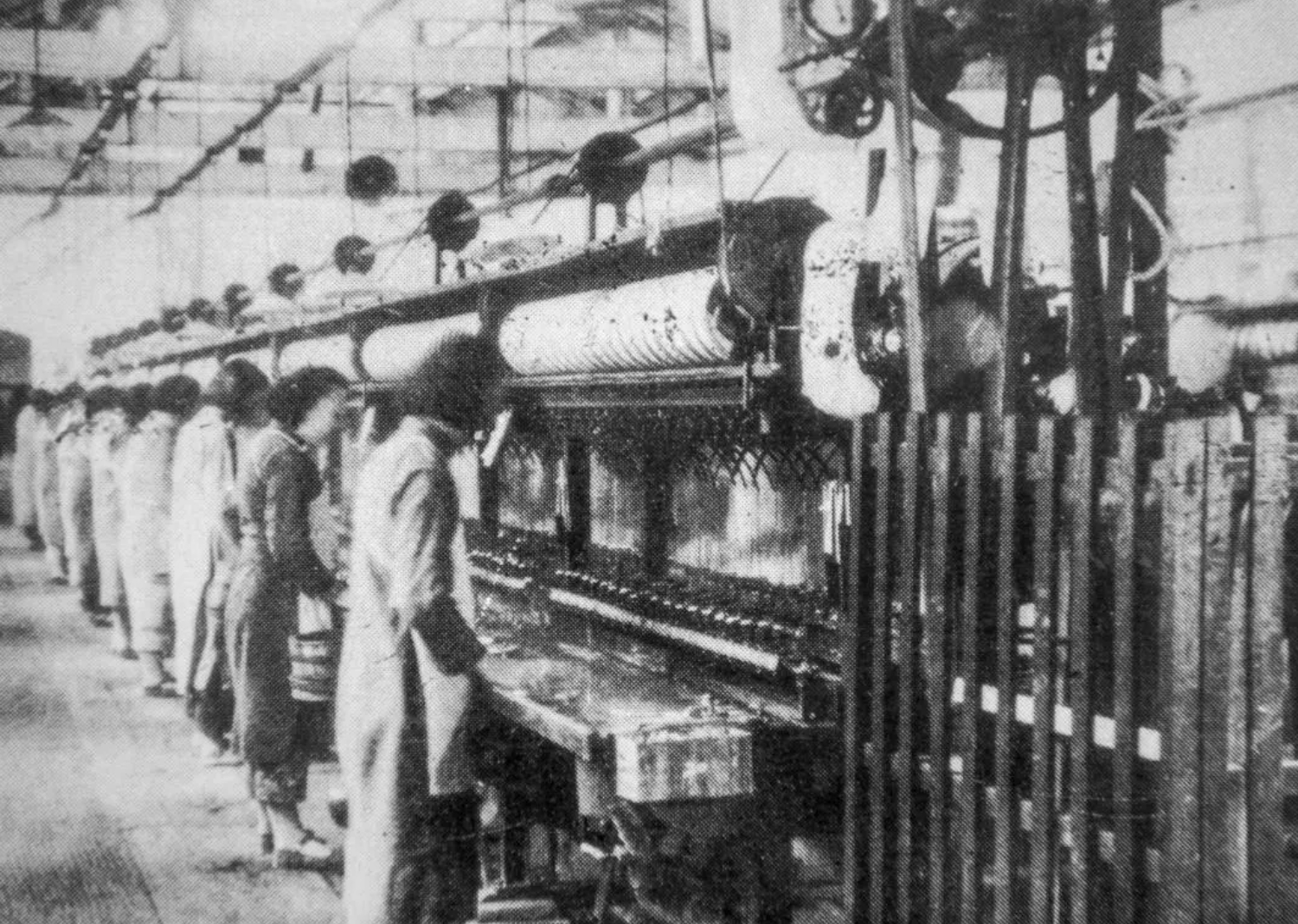

Research by Luxe.CO also shows that raw silk ranked among China’s top export commodities in the first half of the 20th century—during the early years of the Republic of China. This gave rise to a number of companies, such as the Yongtai Silk Reeling Factory in Wuxi and the Mayar Silk Weaving Mill in Shanghai. Varieties such as Jiangsu’s “White Factory Silk” and Zhejiang’s “Lake Silk” were highly sought after on international markets for their superior quality.

Above: The Yongtai Silk Reeling Factory in Wuxi, established in 1896, developed China’s first multi-spindle automatic reeling machine in 1930.

“White Factory Silk” refers to machine-reeled raw silk, in contrast to traditional hand-reeled “native silk.” The factory’s “Golden Deer” brand, White Factory Silk, became one of the most recognized products. Mechanized production ensured uniformity and consistency in the silk threads, reducing batch discrepancies commonly found in handmade processes and thereby increasing reliability in textile manufacturing.

Huzhou silk has been renowned throughout China since the Ming Dynasty, with the finest quality coming from Jili Village in Nanxun Town. “Jili Lake Silk” was produced from lianxin (“lotus-heart”) silkworm cocoons, which were small but yielded silk that was both delicate and strong—so strong, in fact, that a single thread could pass through eight copper coins. In 2011, the handcrafting technique of Jili Lake Silk was officially listed as part of China’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Above: Jili Lake Silk. Source: WeChat account of Huzhou Nanxun District Library.

According to a report published by Phoenix News titled “A Study on Changes in the Structure of China’s Imports and Exports in the Early Republic of China,” China exported over 435,000 dan (a historical Chinese unit of weight) of raw silk in 1928, with a total value of 159.75 million Haikwan taels. In 1929, although the export volume slightly declined, the total value rose to 164.2 million Haikwan taels, indicating an increasing share of high-quality, higher-priced silk. However, after 1930, due to the impact of warfare, China’s raw silk exports suffered severe setbacks.

An article published in Guangming Daily in 2022 titled “Sino-American and Sino-French Silk Trade and Cooperation in the Early 20th Century” noted that during World War I, France launched the Lyon International Sample Fair (also known as the Lyon International Fair), which served as a direct trade platform for manufacturers and merchants. The fair featured a wide range of goods, among which textiles stood out the most.

In March 1920, five Chinese representatives attended the Lyon International Sample Fair, including Liao Shigong, the Consul General in Paris, and Lu Shiyin, editor of The Chinese Labor Weekly published by the YMCA of Paris. Beyond exhibiting Chinese goods, they engaged extensively with the Lyon municipal government, the Silk Merchants Association, and the French Chamber of Commerce. They also toured textile factories and silk machinery companies, solicited feedback on Chinese silk from French merchants, and discussed the improvement of Chinese silk and the establishment of a direct Chinese trade agency abroad.

So then, which was the most favored type of raw silk among the many exported during the Republican era?

According to China’s Silk Trade: Traditional Industry in the Modern World, 1842–1937, a scholarly work by Professor Lillian Li of Swarthmore College, the most renowned export variety was a silk known as Tsatlee, named after the town of Jili in Nanxun, Huzhou. Huzhou, located in northern Zhejiang, was a central hub for sericulture. However, as Tsatlee silk was typically hand-reeled by local farming households, its quality was inconsistent. For export purposes, the silk generally underwent secondary processing. It first appeared in Chinese customs statistics in 1910.

According to Wikipedia, after China opened five treaty ports in 1842, Nanxun Town in Huzhou became the country’s largest raw silk distribution center. Between 1880 and 1934, the town exported an average of 5,420 bales of raw silk annually.

Luxe.CO also discovered a 1912 sample of Tsatlee silk from Huzhou in the online collection of the Smithsonian. The sample, held by the National Museum of American History, confirms that Tsatlee silk was indeed favored by foreign buyers and well-known internationally during the Republican era.

The remarkable tensile strength of Hermès’ first scarf strongly aligns with the characteristics of Tsatlee silk. Combined with trade records from the Republican era, Luxe.CO boldly speculates that the silk used in Hermès’ first scarf in 1937 may have originated from Jili, Nanxun, in Huzhou.

Above: Screenshot from Hermès’ official website.

From its first carré Jeu des Omnibus et Dames Blanches, Hermès gradually built a complete ecosystem for scarf production, creativity, and craftsmanship, eventually establishing a dedicated silk scarf factory in Lyon, France.

According to Luxe.CO research, Hermès currently sources its raw silk primarily from Paraná, Brazil.

In a significant 2007 interview with The New York Times, then-CEO Patrick Thomas stated:

“We do source our raw silk from Brazil, but we weave it ourselves in France, we print it ourselves, and we hand-roll it ourselves.”

Luxe.CO also accessed a report titled “Hermès’ Silk Supply Chain: Impacts on Biodiversity,“ written by the University of Cambridge in 2020, available on Hermès’ official website, which offers further insights.

The report revealed that in recent decades, Hermès has been sourcing silkworm cocoons from smallholder farmers in Paraná, Brazil, through local partners. Hermès’ partner in Brazil is the country’s only raw silk export company and a member of the United Nations Global Compact.

Luxe. CO’s Silk Culture column will explore more details about Hermès’ craftsmanship and supply chain collaboration in an upcoming article—stay tuned.

About Luxe. CO’s Silk Culture Division

In March 2025, Luxe.CO officially launched the Silk Culture Division to promote the richness and potential of Chinese silk culture to high-level industry readers worldwide. The initiative aims to foster a deeper understanding of China’s silk heritage and explore pathways to revitalize and modernize the silk industry.

Beyond delivering original high-quality content, Luxe.CO will also organize a series of curated cultural and industry initiatives, including traceability journeys, forums, workshops, and cultural exhibitions. Guided by first-principles thinking, the initiative aims to trace silk back to its origins—bridging culture and commerce, material and technique, history and present, China and the world—while uncovering and interpreting the essence of silk craftsmanship through a fresh perspective.

Contact for Luxe.CO Silk Culture Division: silk@luxe.co

| Image Credit: Hermès official website; Britannica; Official website of the Wuxi CPPCC; WeChat account of the Nanxun District Library, Huzhou; Smithsonian website

| Editor: LeZhi