The origins of silk weaving can be traced back to ancient times, and Sichuan, China, is recognized as the birthplace of this global craft. In fact, the world’s first high-end silk fabric—one of the earliest luxury goods—originated in Chengdu, Sichuan. This fabric is known as Shu Brocade (蜀锦).

But the connection between Shu Brocade and Sichuan, particularly Chengdu, runs deeper than you might imagine!

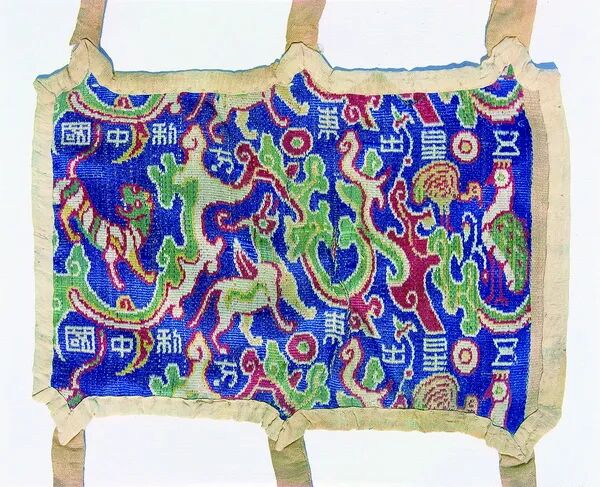

Above: Shu Brocade is known for its durability and sculptural texture, with patterns that stand out in relief against a smooth and soft silk background. Under even the slightest light, its colors shift and shimmer, creating a dazzling effect.

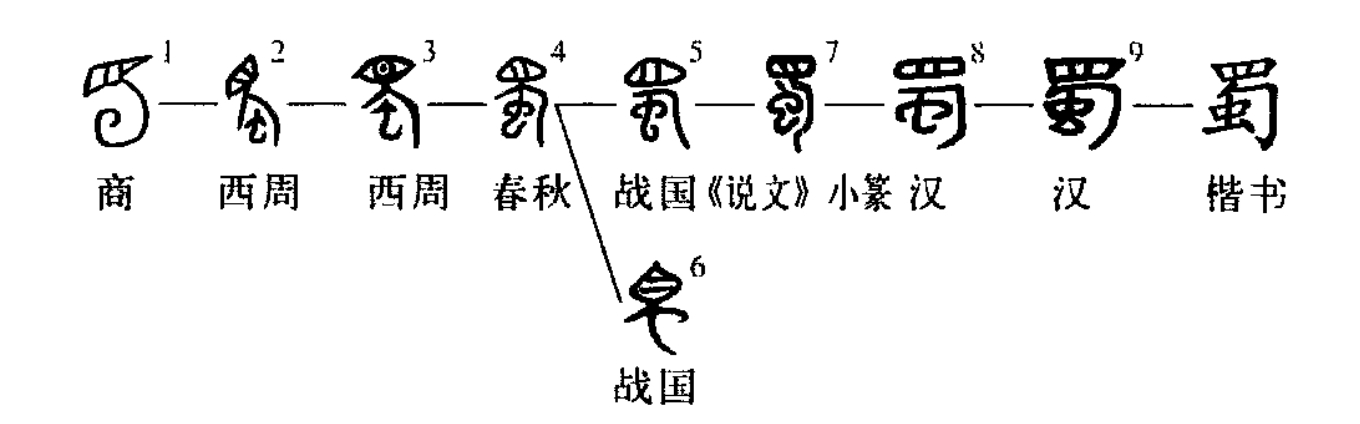

In Chinese, the character 锦 (jǐn) generally refers to multicolored patterned silk fabrics. However, few people know that the abbreviation for Sichuan, “Shu” (蜀), is actually a pictographic character derived from the appearance of a silkworm. According to the ancient Chinese dictionary Shuowen Jiezi, “蜀,葵中蚕也。从虫,上目象蜀头形,中象其身蜎蜎。” This means that the character “蜀” symbolizes a silkworm’s shape, with its head and body depicted in motion.

Image source: Baidu Baike

For over two thousand years, Shu Brocade has been a vital part of Sichuan’s economy. Today, it has evolved into a hidden yet deeply ingrained cultural legacy that continues to shape the local way of life.

Sichuan: The Birthplace of Global Sericulture

The earliest known inventor of sericulture (silkworm farming) emerged in Sichuan 5,000 years ago.

According to Records of the Grand Historian (史记), the legendary Yellow Emperor (Huangdi), considered the ancestor of Chinese civilization, had a primary wife named Leizu (嫘祖). She was born in the Xiling Tribe of ancient Shu (now Yanting County, Mianyang, Sichuan). Leizu is credited with inventing the art of raising silkworms, earning her the title “First Silkworm Goddess” (先蚕) and “Silkworm Deity” (蚕神) in Chinese history. Her efforts, along with those of her descendants over generations, laid the foundation for Sichuan’s sericulture industry, which eventually gave rise to Shu Brocade—a forerunner of brocade weaving worldwide.

Above: Yanting County. (Image source: Yanting Government WeChat Public Account)

Shu Brocade originated during the Han Dynasty (over 300 BCE). Many other types of silk fabric that later emerged across China were actually developed by Shu Brocade artisans. This is why Shu Brocade is often referred to as the “Mother of All Brocades” (万锦之母).

Sichuan’s natural environment played a crucial role in the development of Shu Brocade. During the Qin and early Han dynasties, China entered its second climatic warm period. The region’s fertile soil, mild climate, and stable irrigation system (thanks to the Dujiangyan water project) provided ideal conditions for silk production. Moreover, the rugged Sichuan mountain roads (“Shu Roads”) acted as a natural barrier, protecting Shu Brocade’s craftsmanship from external influence. Additionally, the vibrant colors of Shu Brocade were made possible by the natural mineral dyes found in Sichuan’s river basins.

Chengdu: The “City of Brocade”

Chengdu is often referred to as “Jincheng” (锦城), or the “City of Brocade”—a legacy that still permeates the city today.

The famous line from Du Fu’s poem Spring Night Rain (《春夜喜雨》) “晓看红湿处,花重锦官城,” translated to mean “At dawn, the rain-soaked reds appear, the flowers weighed down in Brocade Officer City.” “锦官城” (Jinguan City) is an old name for Chengdu, referring to its historical connection to Shu Brocade production.

The term “Jinguan” dates back to the Western Han Dynasty, when a government office, Jinguan (锦官), was established to oversee Shu Brocade production, levy brocade taxes, and regulate trade. The administrative office and imperial workshops were concentrated in “Jinli” (锦里)—now the bustling commercial district around Wuhou Shrine. Shu Brocade was also closely associated with the Jinjiang River (formerly known as “Zhuojin River,” or “River for Washing Brocade”), Jinguan Post Station (锦官驿, now located in Jinjiang District), and Cujin Town (簇锦镇, now Cujin Street)—historical centers for brocade production and trade.

Above: Jinjiang District, Chengdu. (Image source: Chengdu Government WeChat Public Account)

Today, Chengdu residents are accustomed to seeing place names that include the character “锦” (jin, meaning “brocade”). The influence of Shu Brocade has become deeply embedded in the city’s culture, leaving an indelible mark on everyday life.

Shu Brocade: Zhuge Liang’s “Hard Currency”

Shu Brocade originated in the Han Dynasty and became a crucial economic pillar of Sichuan, evolving alongside the region’s history for over two thousand years.

Above: Statue of Zhuge Liang at Wuhou Shrine, Chengdu. Image source: Chengdu Wuhou Shrine WeChat Public Account.

In Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Zhuge Liang launched five Northern Expeditions despite the economic hardship in Yizhou (present-day Sichuan). One key factor that made this possible was Shu Brocade.

Historical records in The Collected Works of Zhuge Liang (诸葛亮集) state: “Now the people are poor, and the state is weak; for war expenses, we must rely on brocade.”

Recognizing its strategic value, Zhuge Liang encouraged large-scale mulberry planting and sericulture development, using Shu Brocade as both a diplomatic gift and an international trade currency. It was directly exchanged for grain, warhorses, and weapons with Eastern Wu, Cao Wei, and even regions in the Western Regions (Central Asia), providing critical financial support for military campaigns. In essence, Shu Brocade became an essential strategic resource during the Three Kingdoms period.

Throughout history, Shu Brocade has played a vital role in trade, diplomacy, and economic development while remaining a luxury favored by royalty and nobility—a status vividly portrayed in popular TV dramas such as Empresses in the Palace (甄嬛传).

Shu Brocade: The “High-Tech” Craft of the Ancient World

The intricate weaving process of Shu Brocade is both time-consuming and highly specialized, involving more than ten different crafts and 50 to 60 steps. From pattern design to the actual weaving process, it typically requires seven to eight artisans, with production taking anywhere from several months to several years—hence the saying “an inch of brocade is worth an inch of gold” (寸锦寸金).

Recently, Luxe.CO visited the Chengdu Ancient Shu Brocade Research Institute. According to Jiang Liping, the institute’s production director, traditional wooden looms could only weave a few centimeters of fabric per day, but with technological improvements, modernized looms now increase daily output to 80–100 centimeters, significantly expanding the fabric’s width.

During weaving, artisans meticulously interlace multiple warp and weft threads, creating patterns that resemble dancing silk strands. Precision is key—even a minor flaw can diminish the entire brocade’s value. This meticulous and structured weaving process has earned Shu Brocade the nickname “high-tech craftsmanship of the ancient world”.

Jiang Liping vividly described it: “It’s like computer programming—you must follow a structured process. If you think of warp threads as 0s and weft threads as 1s, you’ll realize just how fascinating the weaving of Shu Brocade truly is.”

Shu Brocade in the 21st Century: What Do Young People Like?

How can this top-tier craft capture the interest of younger generations? The answer lies in innovative patterns—each era’s Shu Brocade designs may seem unconventional compared to previous ones, but they always reflect contemporary cultural trends.

Currently, the Chengdu Ancient Shu Brocade Research Institute has developed over 1,000 unique patterns and has begun collaborating with brands and individual designers to create fresh designs.

At the end of 2024, the institute unveiled a collaboration with Li Ziqi, the renowned traditional culture influencer and one of China’s top KOLs. After a three-year hiatus, Li Ziqi made her first public appearance wearing a white Shu Brocade dress featuring a panda motif, sparking widespread interest among young audiences.

The dress design blends traditional Chinese cloud patterns with panda imagery, reflecting both cultural heritage and Chengdu’s contemporary aesthetic.

Above: According to the institute’s official store, the “Panda Brocade” fabric (1 meter) is priced at RMB 2,680 (approximately USD 370), with a minimum purchase unit of 0.1 meters.

Learning the art of Shu Brocade is a long and rigorous process, requiring five to six years just to master basic techniques. To prepare for this collaboration, Li Ziqi spent more than six months studying the craft. The pattern was co-designed by Li Ziqi, master weaver Hu Guangjun, and his apprentices Chen Xingyu and Jiang Liping.

However, producing the “Panda Dress” was no easy task. Each color combination underwent more than 20 rounds of adjustments, with color calibration alone taking over a month.

The preservation of intangible cultural heritage remains a major challenge. Currently, the number of artisans who truly master Shu Brocade weaving in Sichuan is in the single digits.

Jiang Liping expressed hope that more young people will be inspired to learn Shu Brocade craftsmanship, ensuring that this precious art form continues to thrive in the modern era.

About Luxe. CO’s Silk Culture Division

In March 2025, Luxe.CO officially established the Silk Culture Division, focusing on promoting Chinese silk culture. The goal is to provide high-end industry readers with a deeper understanding of China’s profound silk heritage and immense potential, while fostering discussions and advancements in the revitalization and modernization of the Chinese silk industry.

In addition to consistently producing original high-quality content, Luxe.CO will also launch a series of carefully curated cultural and industry events, including heritage discovery tours, forums and workshops, cultural and art exhibitions, and more. Following first-principles thinking, the division will trace silk’s origins—from culture to commerce, materials to craftsmanship, history to the present, and China to overseas markets—integrating the entire industry chain to uncover the essence of silk culture and craftsmanship, and interpreting and spreading it from a fresh perspective.

Luxe.CO Silk Culture Division Contact Email: silk@luxe.co

| Image Credit: Luxe.CO photography; Chengdu Ancient Shu Brocade Research Institute (Xiaohongshu account); Yanting Government WeChat Public Account; Chengdu Government WeChat Public Account; Chengdu Wuhou Shrine WeChat Public Account; Baidu Baike

| Editor: Maier

![From Luckin Collaboration to Debut in Italy, Shu Brocade Goes Viral This Summer! [Luxe.CO Silk Culture Column]](https://cdn.luxeplace.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/%E5%BE%AE%E4%BF%A1%E5%9B%BE%E7%89%87_20250828141820_343_3.jpg)